Are you in Manhattan, or Georgetown, or on a college campus? Or just care about why we invaded Iraq? You may be surprised to find out that, as Joe Scarborough explained this morning on MSNBC, you’re not an American.

OBAMA: I do know Al Qaeda’s in Iraq, and that’s why we should continue to strike Al Qaeda targets, but I have some news for John McCain. And that is that there was no such thing as Al Qaeda in Iraq before George Bush and John McCain decided to invade Iraq. They took their eye off the people who were responsible for 9/11 — that would Al Qaeda in Afghanistan, which is stronger now than at anytime since 2001. I’ve been paying attention, John McCain.

GEIST: So are you ready for eight months of that argument?

SCARBOROUGH: Well, you know, it is an argument — Mika’s gonna disagree with me on this one — but I would guarantee you, guarantee you, that while a lot of people in Manhattan and Georgetown and on college campuses are worried about what happened in 2002 and the lead up to the war, Americans are concerned about what’s happening now.

It’s amazing how many people there are prancing around who aren’t Americans. For instance, in December, 2005, 56% of Americans un-Americanically believed it was “very important” for Congress to investigate the way we went to war. By June, 2006 (the most recent poll I can find) that number was still steady at 57%.

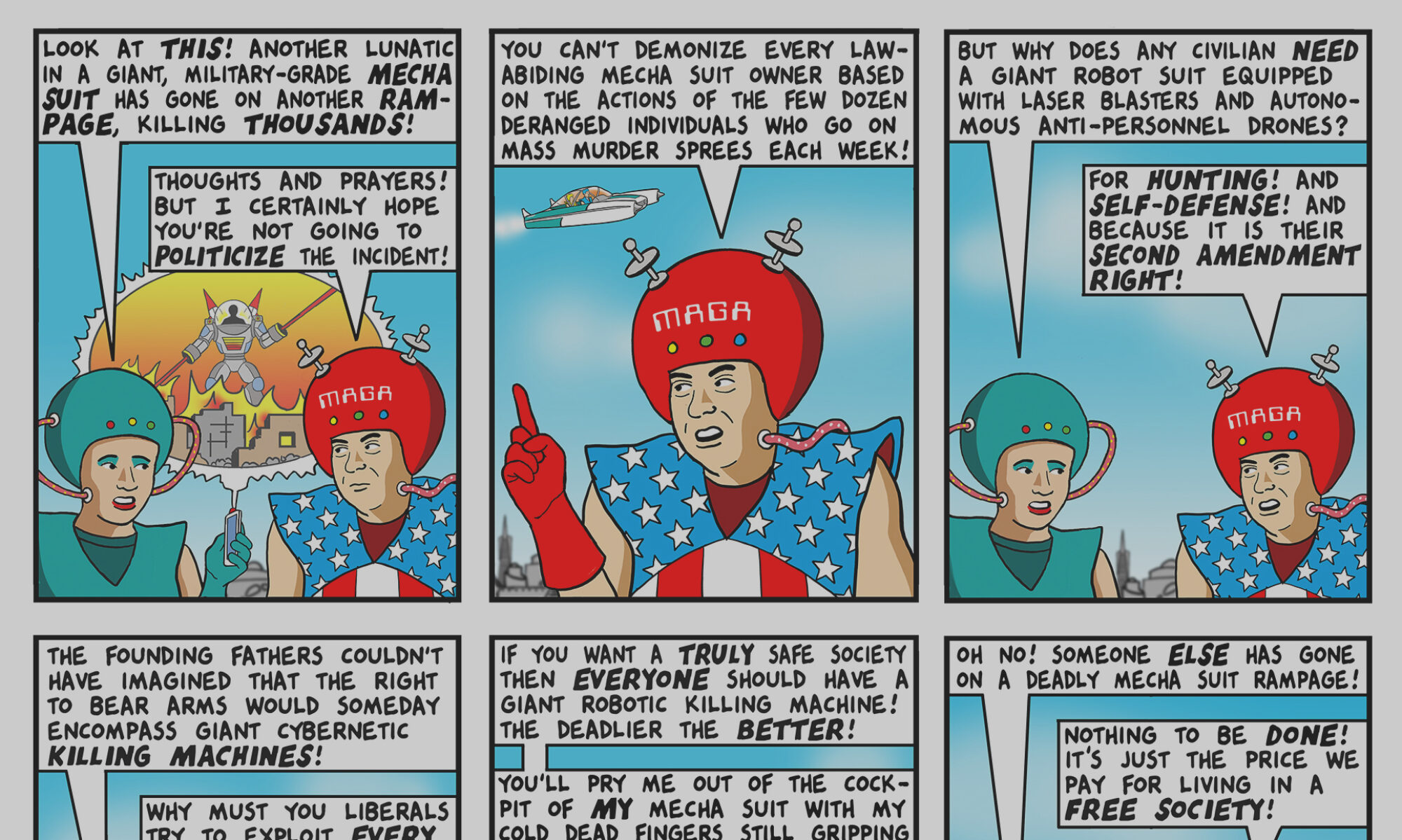

It’s a lot of fun to imagine what would happen if someone on MSNBC said, “I guarantee you that while a lot of white boys in Alabama and rural Texas are worried about laws banning hand guns, Americans are not.”

If you want to express your opinion to MSNBC, Democrats.com has set up something here.